i went to a conference in nairobi, kenya at the beginning of september. i was staying at a home on the southwest side of the city (very graciously hosted by the Mukolwe family), and much of my time there was spent taking public transit the twelve miles to the conference site (average commute time: over an hour and a half). the conference was the nilo-saharan colloquium. it is a venue for researchers to present linguistic research involving languages belonging to the nilo-saharan language family. this language family doesn't include a lot of languages that most people in america know about--the best known nilo-saharan languages probably include dinka, which is (along with less-well-known nuer) the language of many of "the lost boys" from south sudan (and nba players such as Manute Bol and Luol Deng), luo, the native language of Barack Obama's father, and perhaps kanuri, an important language in nigeria. there are some groups of languages that all seem pretty clearly to be members of a single language family, and there are several other languages that scholars disagree about--do they belong to the nilo-saharan language family, or should they be considered separate language families? the kuliak languages, which i study, are one such group. the nilo-saharan colloquium takes a very ecumenical approach--marginal members of nilo-saharan are mostly welcome. i presented a paper about plural marking in nyang'i, the language that i research, but without a doubt the best part of the experience was spending time with other scholars, particularly my friend Terrill, who has worked to describe the ik language (one of the closest relatives of nyang'i), befriend the ik people, and advocate for the ik community for years.

the last day of the conference involved no papers--conference participants who desired to were picked up at the conference venue by a school bus and driven into nairobi national park, a surreal 46 square mile stretch of savanna abutting the southern edge of the largest and most developed city in east africa. enormous herds of free-ranging zebras leisurely chew grass against a modern urban backdrop. lions stalk through tall grass. ostriches ostrich around, looking ostrichly awkward.

school buses are not the best mode of transportation for the purposes of discreetly sneaking up on critters or for feeling like one has ventured into the unexplored wilds. but the city skyline put a damper on that last bit from the get-go, and the critters seem acclimated enough to loud vehicles. this coke's hartebeest (kòmé or òmá in nyang'i--i wasn't able to get distinctions between subspecies of hartebeest) (i think that identification is right?) was content to stare us down.

there are some pools fairly deep into the park that are known for having hippos. at this point, visitors to are allowed to get out of their vehicles and go on foot, under the condition that they have an armed escort (employed by the park). this was certainly the most enjoyable part of the tour to me. i was no longer shooting down at the animals that i was photographing, and i no longer felt the separation from my experience provided by the steel, glass, and plastic of the bus. antelope spied on me from the bushes. i think that this particular species is the waterbuck (múɲ), but i'm out of my element.

this bushbuck (mur) leisurely grazed a few yards away from me for a few minutes.

the wildlife had been comfortable enough while we were in the bus, but when we were on foot, it felt less like they were awkwardly having their photo taken. several times from the bus, photographing animals had felt similarly artificial to taking portraits of people. "uhhh what do i do now?" this impala (which probably wouldn't be accurately called òkáíɬ in nyang'i, but that's the closest species i got the name of), on the other hand, just gazed off to the horizon.

a small troop of vervet monkeys (lókàlèpér) wandered through the grass before taking a grooming break.

i found monkey portraits to be difficult because their eyes don't have whites, which makes it hard to expose any detail into them.

the first 45 minutes or hour on the road had been pretty nice. the experience was novel, and we were seeing cool animals doing cool things. the bus driver had been hesitant to come to a full stop, which was a source of frustration. the slowly creeping bus made it difficult for people to take photos (much less to watch what the animals were doing). on the balance, though, people seemed to be having a good time. after the hike, though, many on the bus seemed to grow restless. "will we see lions soon" was a common refrain. we want to see lions. when will we see lions? beautiful wildlife flew by the bus windows. no time to watch. we seek lions. we found lions (méù).

we watched the first adolescent, seen above, for a few minutes, before finding a beautiful lioness lingering in the scrub brush.

she slowly sauntered onto a more sparsely vegetated hillside and glared at us. we had watched her for a few moments.

school buses are not the best mode of transportation for the purposes of discreetly sneaking up on critters or for feeling like one has ventured into the unexplored wilds. but the city skyline put a damper on that last bit from the get-go, and the critters seem acclimated enough to loud vehicles. this coke's hartebeest (kòmé or òmá in nyang'i--i wasn't able to get distinctions between subspecies of hartebeest) (i think that identification is right?) was content to stare us down.

there are some pools fairly deep into the park that are known for having hippos. at this point, visitors to are allowed to get out of their vehicles and go on foot, under the condition that they have an armed escort (employed by the park). this was certainly the most enjoyable part of the tour to me. i was no longer shooting down at the animals that i was photographing, and i no longer felt the separation from my experience provided by the steel, glass, and plastic of the bus. antelope spied on me from the bushes. i think that this particular species is the waterbuck (múɲ), but i'm out of my element.

this bushbuck (mur) leisurely grazed a few yards away from me for a few minutes.

the wildlife had been comfortable enough while we were in the bus, but when we were on foot, it felt less like they were awkwardly having their photo taken. several times from the bus, photographing animals had felt similarly artificial to taking portraits of people. "uhhh what do i do now?" this impala (which probably wouldn't be accurately called òkáíɬ in nyang'i, but that's the closest species i got the name of), on the other hand, just gazed off to the horizon.

a small troop of vervet monkeys (lókàlèpér) wandered through the grass before taking a grooming break.

i found monkey portraits to be difficult because their eyes don't have whites, which makes it hard to expose any detail into them.

the first 45 minutes or hour on the road had been pretty nice. the experience was novel, and we were seeing cool animals doing cool things. the bus driver had been hesitant to come to a full stop, which was a source of frustration. the slowly creeping bus made it difficult for people to take photos (much less to watch what the animals were doing). on the balance, though, people seemed to be having a good time. after the hike, though, many on the bus seemed to grow restless. "will we see lions soon" was a common refrain. we want to see lions. when will we see lions? beautiful wildlife flew by the bus windows. no time to watch. we seek lions. we found lions (méù).

we watched the first adolescent, seen above, for a few minutes, before finding a beautiful lioness lingering in the scrub brush.

she slowly sauntered onto a more sparsely vegetated hillside and glared at us. we had watched her for a few moments.

"let's get breakfast." "i'm hungry."

she hadn't obviously begun to do any tricks, so the attention of many in the bus flagged. scarcely had we begun watching her when we set off to that fabled country called breakfast.

it felt microcosmic of the human condition. we anticipate the next thing. we make sacrifices for the next thing, and we anxiously ignore the present for the sake of getting to the next thing. but when the next thing comes, we quickly grow bored with it. we anticipate the next next thing. we don't linger. we don't watch. we don't reflect. or at least these are things that i do and don't do.

i don't know if this blog is (or was intended to be) a symptom of this problem (for i think that it is a problem). when i consider my purpose for starting it (set forth in my initial post, here), i see a lot of the discontent that robs the present of its richness. but i also see a longing to see and savor these richnesses, and to make choices that make the richnesses easier to find. i don't know, and i don't really know if it matters. i think that the main thing is that i don't want to clamor for breakfast when i could be experiencing the presence of lions.

fortunately, we stopped to chat with some giraffes (gwèc) on our way to breakfast. giraffe tongues are silly.

fortunately, we stopped to chat with some giraffes (gwèc) on our way to breakfast. giraffe tongues are silly.

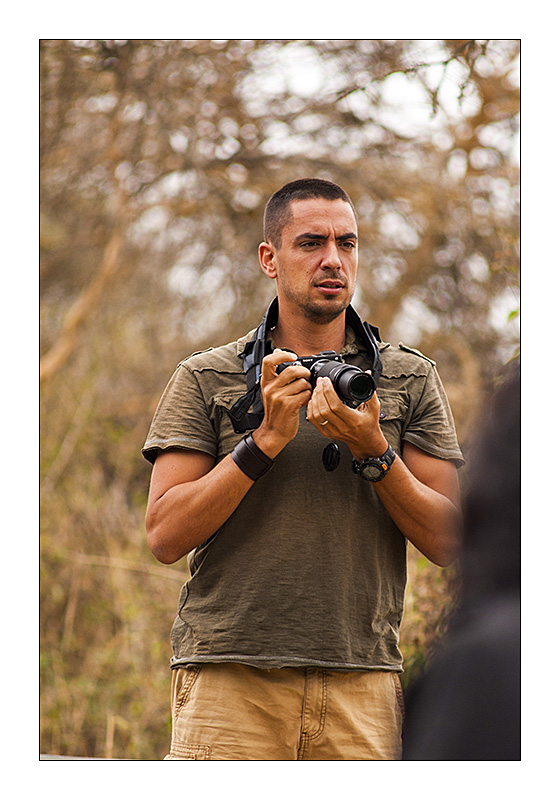

i mentioned earlier that spending time with Terrill Schrock was the highlight of my time in kenya. Terrill personifies so many of the qualities that i long for in my own life. Terrill tends not to clamor for breakfast. he waits and watches. he reflects. he notices the light on leaves, the diversity of grass species in a field. he is patient, kind, and faithful. he is hungry for knowledge and quick to become a student of others. he is willing to teach and a skilled instructor--usually, perhaps, without realizing that he is teaching.

it's because of him that i have done any research in uganda in the past five years. after a brief two month trip working in the soo language, i got in touch with Terrill (who studies the related ik language) to share my results. over time, we emailed about a wide range of things, and he several times encouraged me to do research with nyang'i--which was once thought completely extinct, but which he had found a few remaining semi-speakers of. he has offered me logistical, technical, and emotional support during each of my ensuing research trips. last year he completed his dissertation, a 700+ page opus on the grammar of ik. spending time with him always makes me enjoy linguistic research more, enjoy east africa more, and enjoy being human more.

in the past year or so, he has taken up photography, and the results have been breathtaking.

Osamu Hieda has been studying western nilotic languages in uganda for over 30 years. he is quick to smile and eager to encourage fledgling young scholars (like me) onward in our pursuits. i had never interacted with him before this conference, but greatly enjoyed the conversations that we had.

Torben Andersen is almost certainly the most prolific scholar of the dinka language (also western nilotic). i've been citing his papers in classes that i teach for years. he's soft-spoken, thoughtful, and reserved. i hear about other academic conferences--about the egos, the conflict, and the politics--and i feel really nice about my corner of the scholarly world. there are some egos in the nilo-saharan world. there is some conflict, and there are some silly political squabbles. but the tension and strain are so vastly overshadowed by the combination of graciousness and thoroughness characteristic of participants such as drs. Schrock, Hieda, and Andersen.

No comments:

Post a Comment